During the beginning of the 2016 Spring semester, I travelled to Borneo with 12 faculty and 20 students, mixed evenly from Yale-NUS College and the Claremont Colleges. The expedition was the culmination of over 18 months of planning and was entitled “Envirolabs Asia.” The project was funded by the Luce Foundation, and was awarded to the Claremont Colleges to facilitate interdisciplinary exploration of environmental issues facing Asia. My role was to foster the connection between Yale-NUS and the Claremont Colleges, and I led many meetings between CIPE and the Claremont Colleges between August of 2014 through January of 2015. It was incredibly rewarding to study the group of scholars and students assembled on this trip – faculty from all five Claremont Colleges, representing the disciplines of Music, Media Studies, Biology, Environmental studies, History, Religious studies and Politics. Our team from Yale-NUS included myself, Brian McAdoo (a geologist and expert in disasters and human impacts of earthquakes), Tom White (photographer and documentary film maker), Steven Oliver (Political Scientist and expert on global affairs), Bill Piel (Biology professor and expert on spiders), and also a representative from CIPE. The 8 Yale-NUS students were selected from nominations from faculty and were dynamic, energetic, and similarly diverse in their interests. They took to the trip wonderfully and blended nicely with the 12 Claremont students.

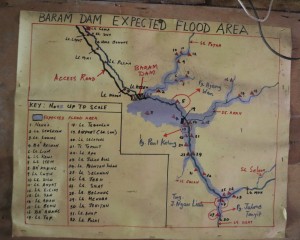

Our trip began in Miri, which is in Serawak – on the Malaysian side of Borneo, just to the west of Brunei. Albert Park, the CMC Envirolabs PI, had arranged for a tour of the Baram River from a fellow named Charles, who has led indigenous people on several activist campaigns to stop construction of dams on the river near his home, and a musician from Kuala Lumpur named Ka Hoe Yii who has worked on compositions inspired by the rainforest in Borneo. Our trip included visits to Palm Oil plantations, stays in long houses with indigenous people (including the Baram Dam protest sites), a tour of the river areas on long boats piloted by indigenous people, visits to small villages such as Long Lama along the river threatened by the dam projects, and many chances to learn from the local people about their lifestyle and the ways in which the forest and river create the culture and livelihood that they depend upon.

The four days in the wilderness included torrential rain, heroic 4WD multi-hour drives through logging roads, and very rustic lodgings which sometimes lacked basic amenities.. We were however rewarded with a rare glimpse inside a fascinating, warm, and beautiful culture and to see some of the complexities facing these people as well. The people would like to conserve their rivershed, but also rely on palm oil cultivation and employment at nearby logging operations for a living. The fishing and subsistence ecology of the region has already been devastated by aggressive logging which has turned the river into a chocolate milk color from sediments. Local people were then forced to find employment downstream at oil companies, or palm oil companies, or upstream at logging operations in many cases. Adding to the complication is an ambiguous indigenous claim to the land surrounding the river, based on old British maps, and weakly enforced by an indifferent Malaysian government office.

We found the time outdoors exciting and found interesting lifeforms – birds, spiders, and other insects were well represented. The stars came out on one night – which enabled a dazzling view of the Milky Way and Magellanic Clouds from central borneo. We had an amazing time zooming along the rivers, floating and swimming in them, and being propelled at mind-bending speeds by the local pilots with their powerful outboard motors! Many great conversations between students, faculty and local people also revealed the interlocking complexity of the environmental, social and political issues facing the Serawak people. It was a challenging, rewarding, and exciting opportunity, and we look forward to further research and collaboration with the Claremont Colleges as part of the Envirolabs Asia effort!