Our Yale-NUS College CTL hosted Deb Pires, Director of the Biology Education program at UCLA, to Yale-NUS College for a series of talks and discussions about STEM teaching. Deb is the Administrator of the UCLA Department of Life Sciences Core Education group, which works with the 17 separate departments at UCLA that are teaching some aspect of life science. She was also one of two founders of the Center for Educational Innovation in the Sciences (CEILS) and has worked for nine years at UCLA as a member of the Educational Technology committee. Deb gave two talks to our faculty, on February 4 and 5, 2016, which were well received and well attended!

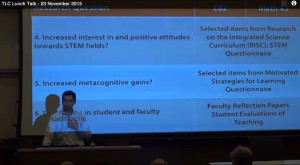

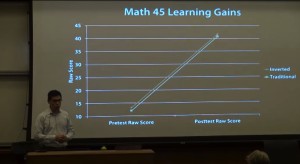

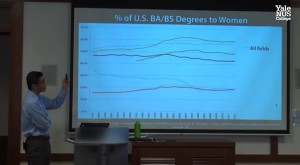

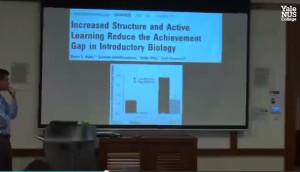

The first talk was entitled “Results from Technology-Enhanced Teaching at UCLA” and discussed how UCLA has been tracking persistence in STEM fields by various demographic groups of students. They are finding very low retention in some groups, and have been working to improve their teaching and curriculum to reverse this trend. She recommended a book “Talking about Leaving – Why undergraduates leave the sciences” by Elaine Seymour and Nancy Hewitt. To motivate the changes in the UCLA curriculum, she cited institutional research data, as well as articles by Haak et al, “Increased Structure and Active Learning Reduce the Achievement Gap in Introductory Biology” and the one by Freeman et al, “Active Learning Increases Student Performance in Science, Engineering and Math.” In her talk she also recommended books by Wood, “Student-Centered Teaching Practices,” and “Leaving the Lectern.”

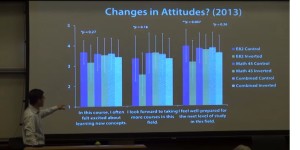

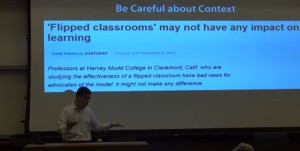

The reforms that they are making at UCLA are described as “high structure” teaching. In this type of teaching, students from more diverse backgrounds are found to perform better than in a traditional form of teaching. The “high structure” includes a pre-class quiz to be sure students are all working on the material out of class. There are active learning activities in class, and also a post-class quiz. Some materials from the course are also “flipped” using the Camtasia program to provide online guides to the readings that allow for the instructor to help students understand the material. To assess the learning they are using concept inventories which she called a “million dollar instrument.” She also did a large number (40-80 hours) of student interviews to allow them to refine the course to overcome confusion within students due to unclear terminology. An important element of the success of the UCLA program are postdoctoral fellows known as the DBER fellows. These are postodocs in biology education, who can mentor some of the senior faculty and help them prepare flipped materials. They also can provide guidance to faculty in constructing explicit Student Learning Objectives (SLOs) which then guide the class activities, and assessments. Getting faculty involved in the project was helped by workshops and with the reminder that contributions for this by faculty would be relevant to their tenure and promotion.

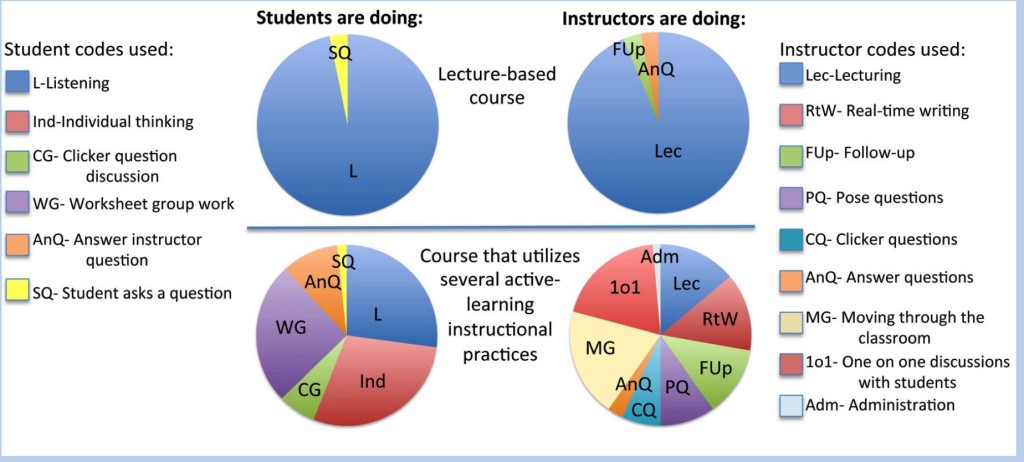

Another very interesting aspect of the UCLA effort was how they were able to incorporate observations of teaching as part of their work. Using an ipad and a program known as the “GORP tool” (which stands for General Observations Reflection Protocol), student associates would be able to catalog in real time what the professor and students are doing in a class. As they observe the class they are able to click on different icons to describe whether the professor is lecturing, asking questions, listening, circulating, or working individually with students. Likewise the students are also observed, and the program records if they are listening, asking questions, writing, discussing, or presenting something. At the end each instructor can see a very nicely produced pie chart of how class time is being used by themselves and by the students. The combination of the intense effort on reaching students, and modifying curriuclum and pedagogy in measurable ways was very inspiring and sounded quite effective.

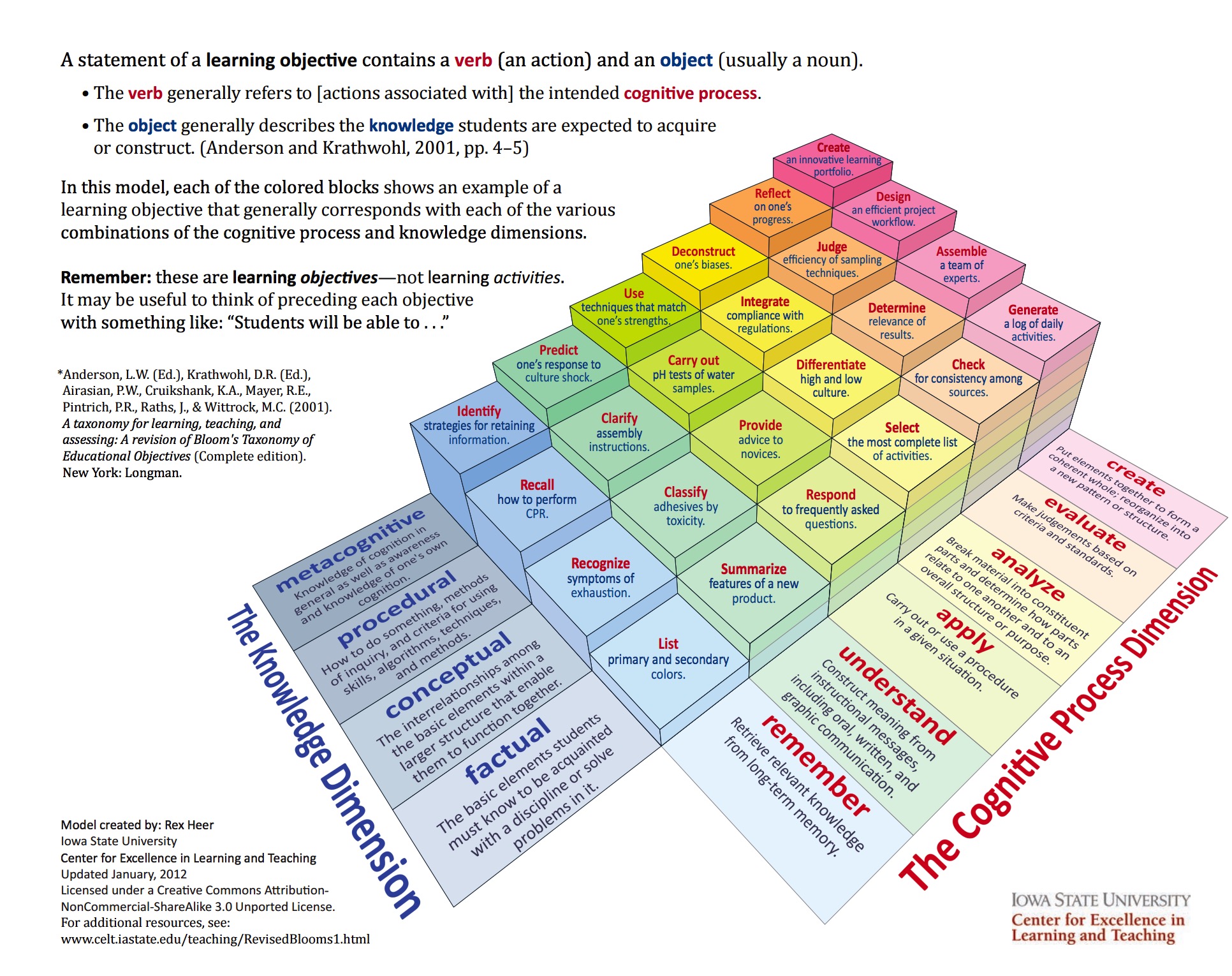

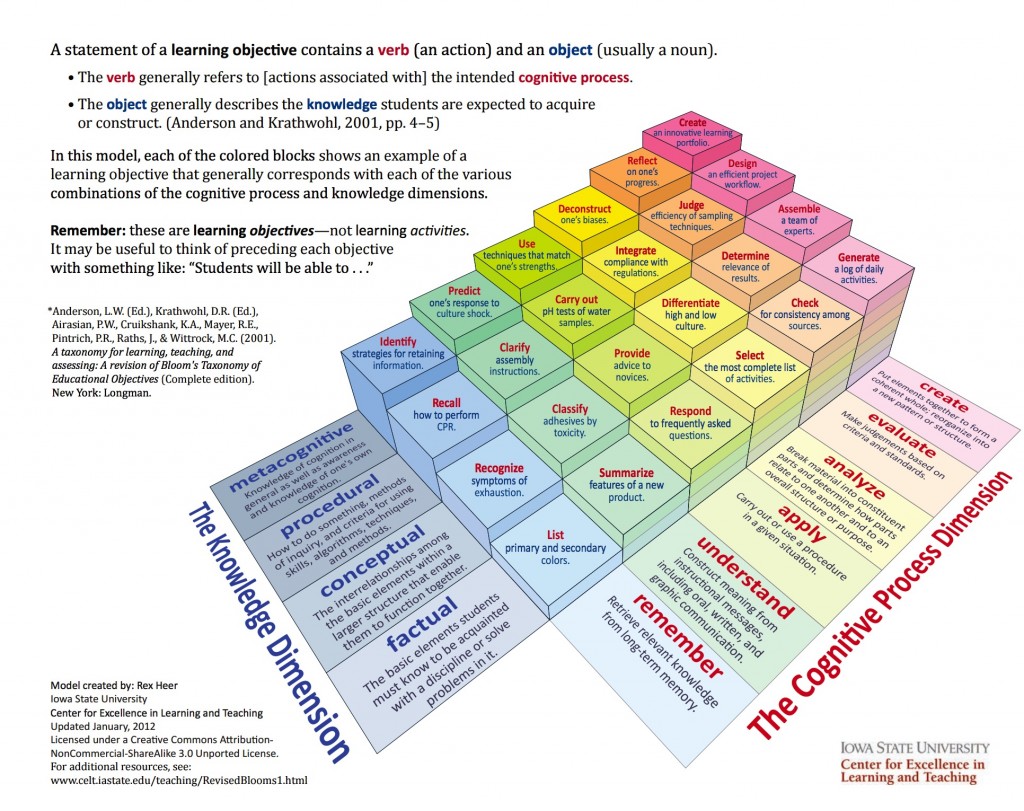

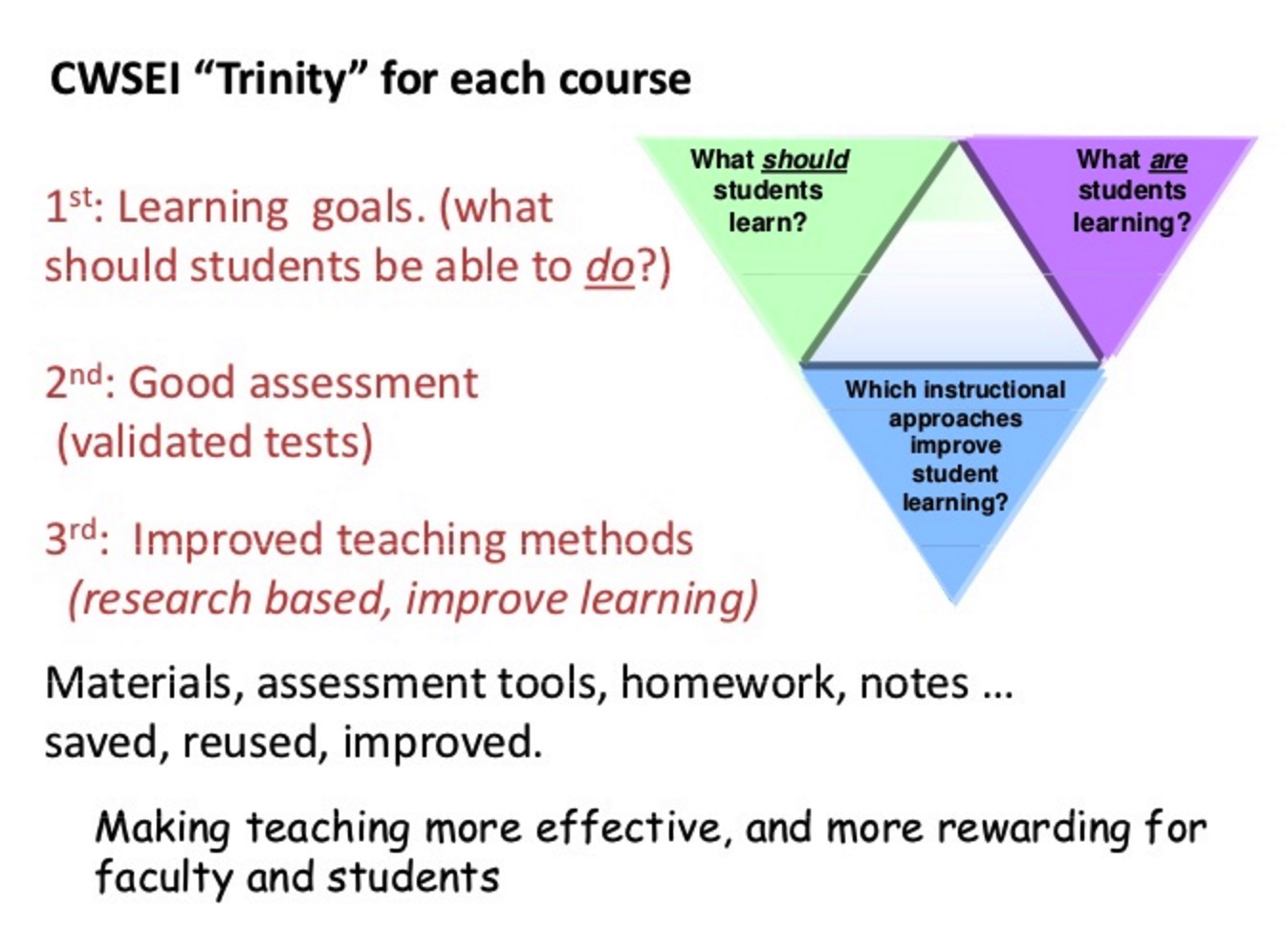

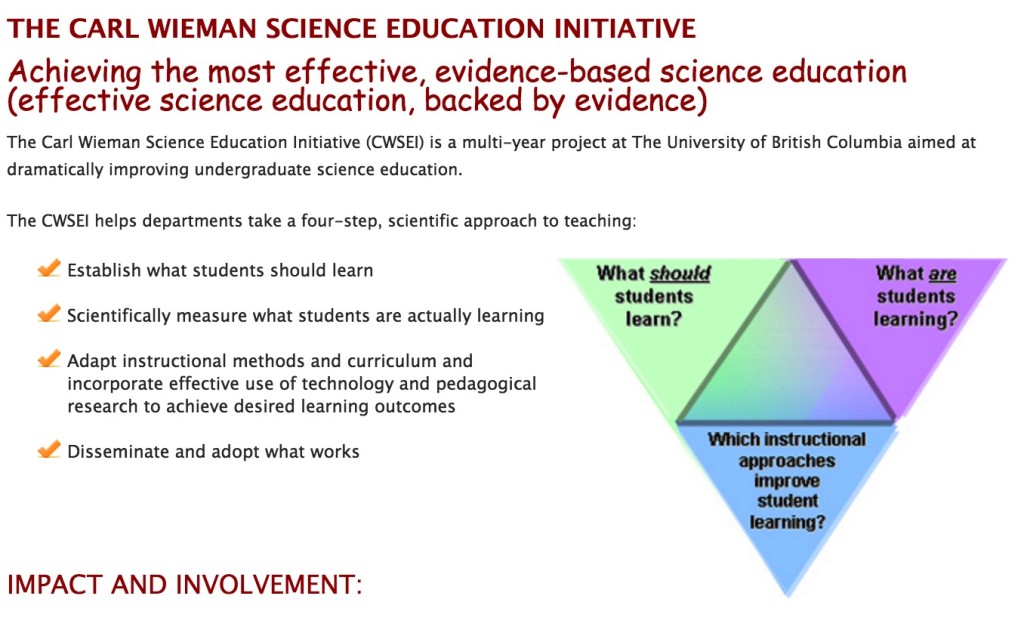

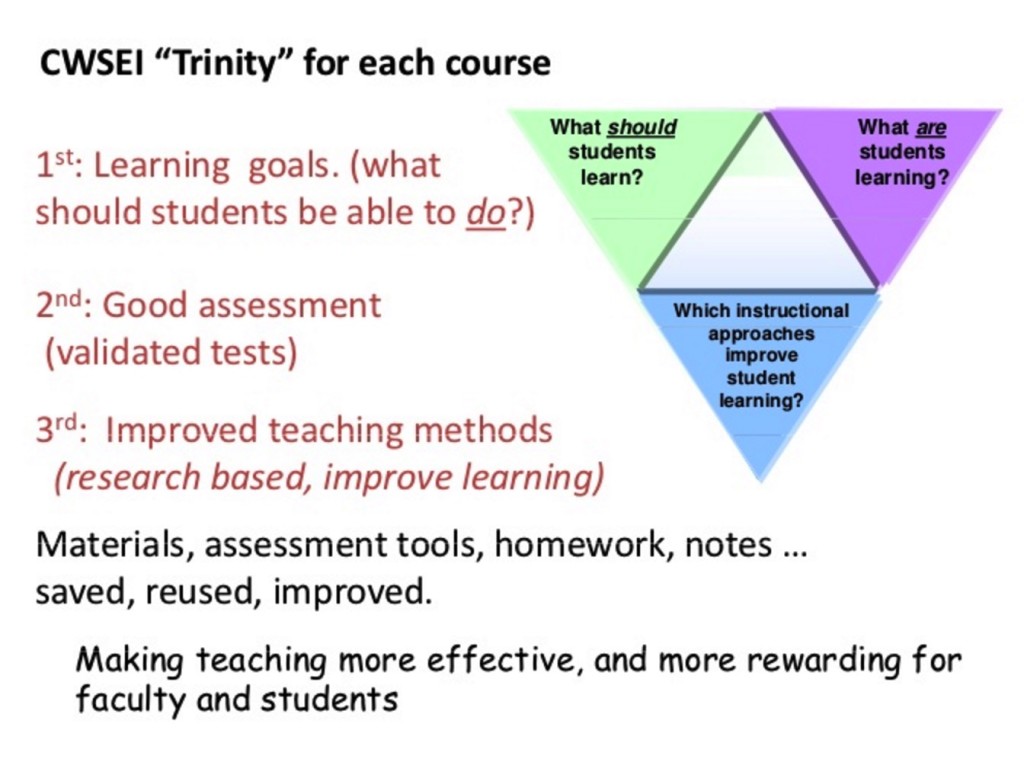

The second talk was about backward course design, learning objectives and how to assess students. The talk was based on the summer workshops that Jo Handelsman used to offer at the University of Wisconsin, and provided a great overview of how to develop a course. The lecture slides are available at our CTL site at this link. Some of the figures below are also from her talk, including the very nice 3D Bloom’s taxonomy figure, developed by the Iowa State University Center for Excellence in Learning and Teaching. It was a very useful session and one that we should over to all of our incoming faculty at Yale-NUS College!