All posts by admin

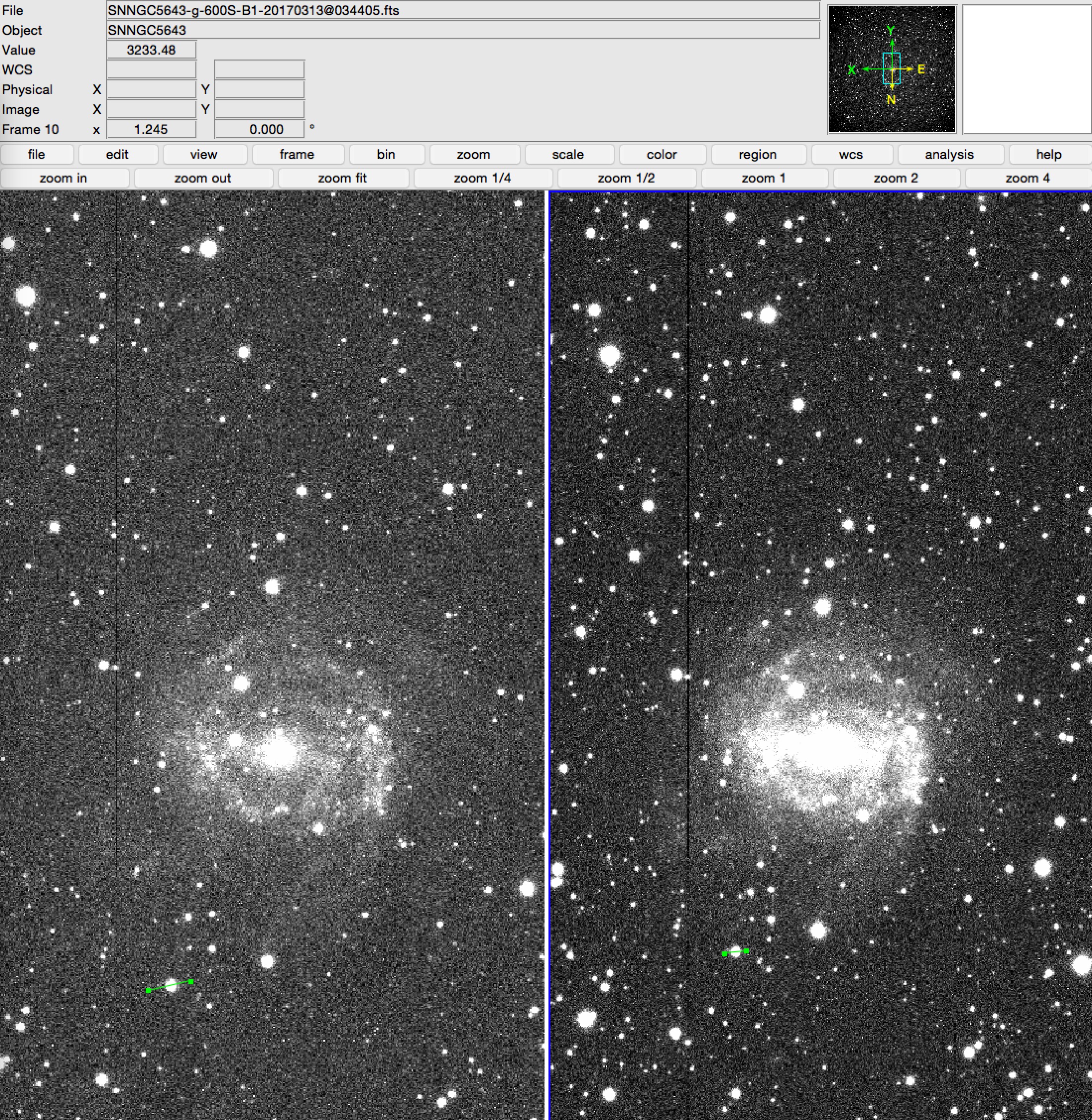

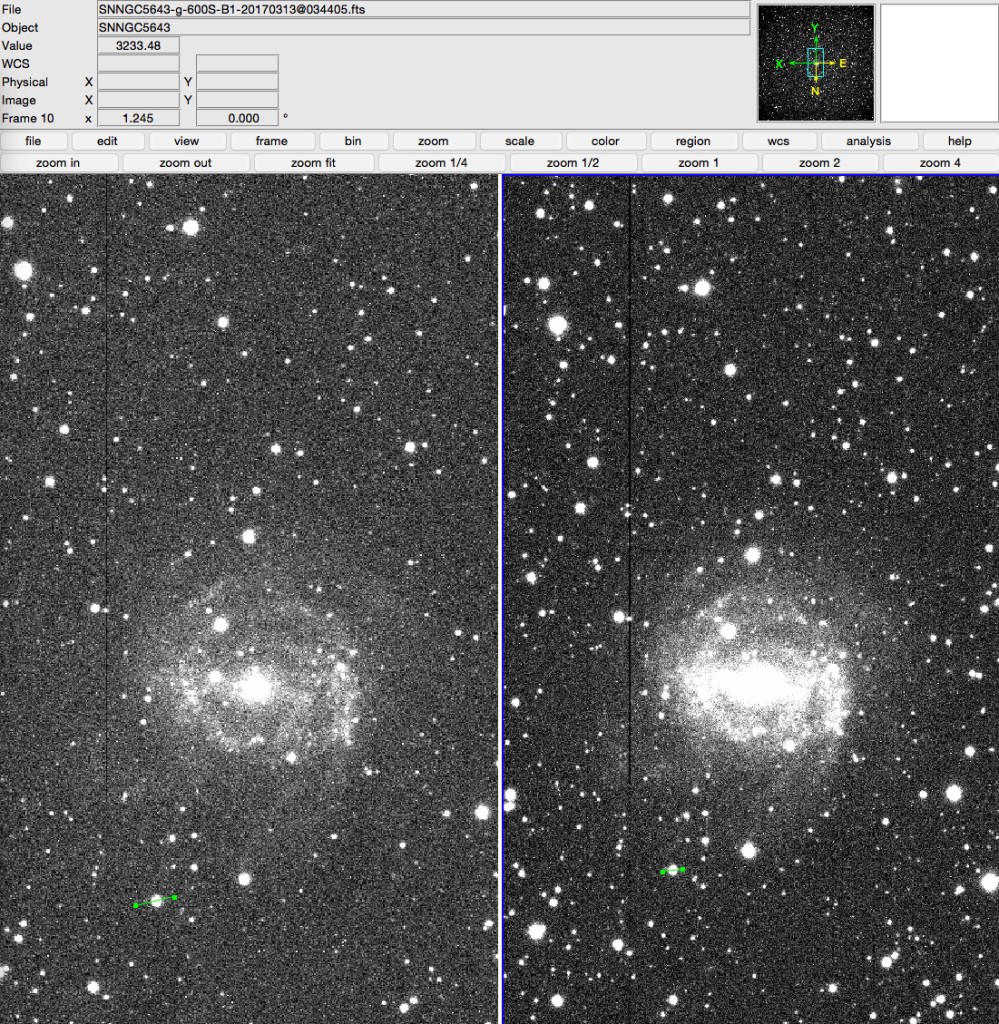

Supernova in NGC 5643!

Institute of Physics Singapore Meeting – Talk on “Cosmic Explosions”

During the Institute of Physics Singapore (IPS) meeting on Feb 22-24 (http://www.ipsmeeting.org/), I was invited to present a talk on “Cosmic Explosions” that related some of the discoveries from our GROWTH relay of telescopes based at Caltech. The talk included a mix of physics professors and students from across Singapore, and it was a great chance to share some of the latest astrophysics results with them. During the talk I highlighted “infant supernovae,” gravitational lensing sources, gamma ray bursts, and the discovery of gravitational waves, and how all of these sources are now possible to catch using telescopes that are optimized for discovering such “transients” and following up the discoveries with a global network of telescopes.

The audience for the talk included a number of students from Yale-NUS College, and as the meeting was hosted at Yale-NUS College, it was also a great chance to help showcase some of the modest astronomical capabilities of Yale-NUS. This includes no only our mighty 0.12-meter telescope and a pair of binoculars, but the Yale 1.3-meter telescope at CTIO and the Carnegie Science LCRO telescope at Las Campanas Observatory, both of which we have been using in our Observational Astronomy course at Yale-NUS College.

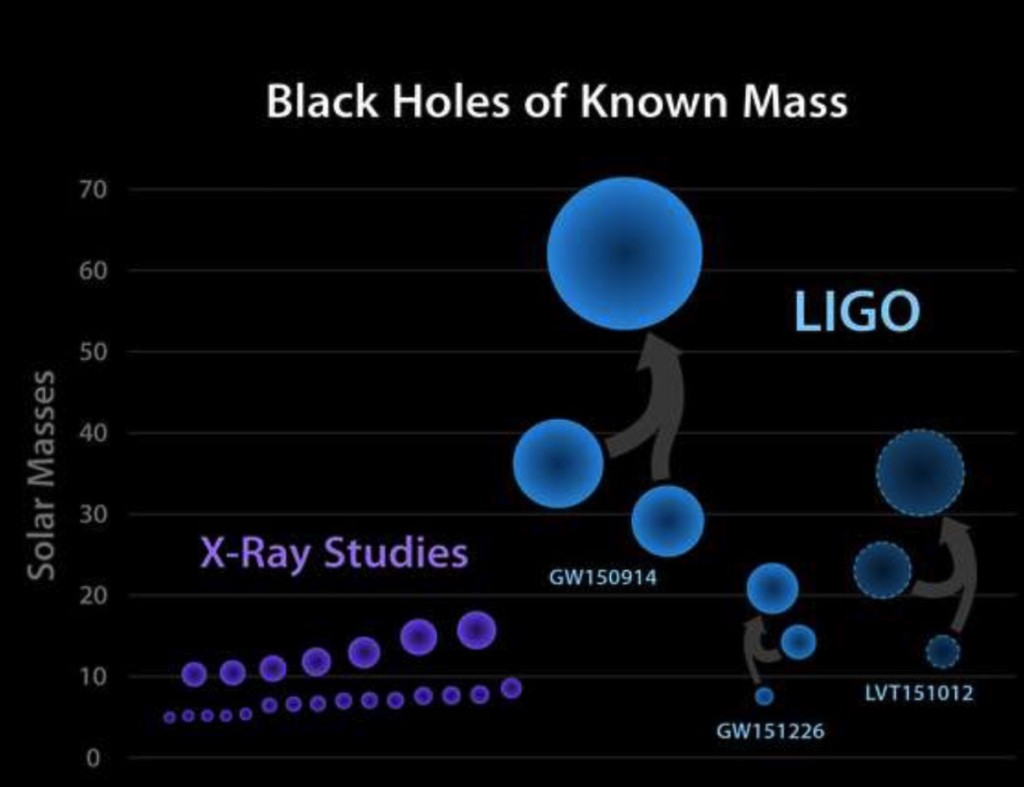

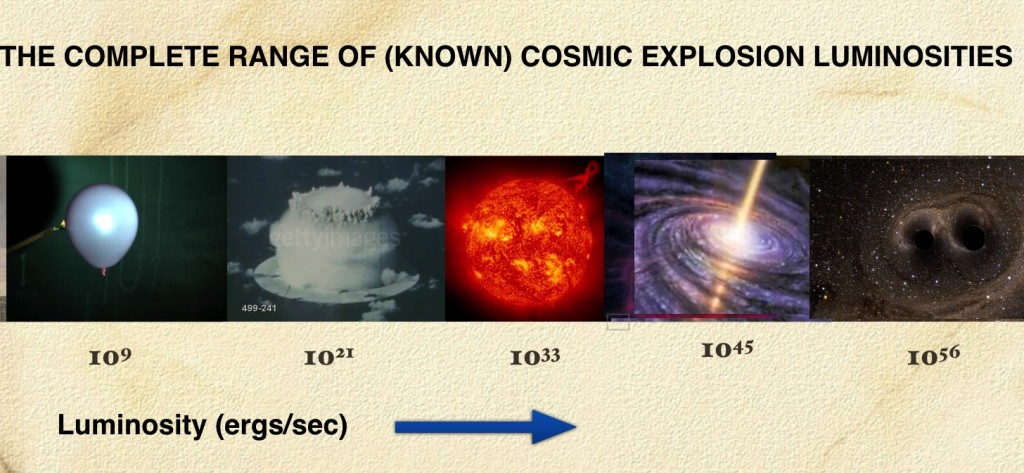

One key takeaway from this talk for me was the astounding energy of the gravitational wave sources discovered by LIGO. Based on their reported data, 3 solar masses of black hole mass were radiated away from the merger of the two black holes within the LIGO GW150914 event, which created a huge black hole over 60 solar masses in size. The energy released by merging the 25 and 37 solar mass black hole exceeds the energy radiated by the most luminous known objects in the universe, the quasar, by a factor of a trillion! The chart of black holes merging and detected by LIGO is shown below (taken from the Caltech press release of Feb 2017), and a diagram showing the range of cosmic explosions is also shown below. Both of these figures were included in my “Chasing Cosmic Explosions” talk along with the background astrophysics of stars, supernovae, gamma ray bursts, and gravitational waves. What an amazing time we live in to have all of these discoveries to study and talk about!

Visit to IIT Gandhinagar and Sudhair Jain

During my visit to Ahmedabad, I was able to visit the visionary Vice Chancellor of IIT Gandhinagar, Sudhair Jain, and learn more about his very interesting campus and its programs. Sudhair was incredibly friendly to me – as I had just arrived without an appointment. Despite the sudden appearance, he warmly welcomed me and my colleague Alicia Contractor, and we discussed many of his new programs in detail in his office over tea.

Sudhair has implemented a wonderful “Foundation Program” for incoming IIT students. The foundation program takes students fresh from their high-pressure high schools, and helps them both unlearn the frantic test-taking mentality that is endemic with IIT admissions, and to learn more about themselves, their context within the society of India, and the larger dimensions of knowledge – including arts, culture and sports.

I first learned about this program from my friends Brian Brophy (a theatre professor from Caltech) and Srini Reddy ( a music professor at IIT Gh). They together taught in the program a couple of years ago, and had students performing music, acting, and exploring the region around the IIT Gh campus. As Srini described it, he would ask his students – “what do you think?” and “what do you feel about this?” and often would receive blank stares back. He joked that students often are under the impression that they are not supposed to think and feel – and the Foundations Program helps them do both.

The goals for the Foundations Program according to the web site include:

- Values and Ethics: Focus on fostering a strong sense of ethical judgment and moral fortitude.

- Creativity: Provide channels to exhibit and develop individual creativity by expressing themselves through art, craft, music, singing, media, dramatics, and other creative activities.

- Leadership, Communication and Teamwork: Develop a culture of teamwork and group communication.

- Social Awareness: Nurture a deeper understanding of the local and global world and our place in at as concerned citizens of the world.

- Physical Activities & Sports: Engage students in sports and physical activity to ensure healthy physical and mental growth.

Sudhair described some new programs he is introducing that go beyond the Foundation program. This includes an IIT Gh Explorers Fellowship program, which gives students a small grant to visit at least “6 states in 6 weeks” – traveling inexpensively, using non-AC trains and busses to see the country of India in depth. Some of the students are able to visit many more states, and in the process they are able to become more aware of life across India to help them become more effective as leaders and as engineers. In a blog posting from Manaal Bhombal, Sudhair Jain describes the goals of the program:

“The fellowship is not just to give students a taste of adventure, it is to engulf them with ground level realities of our country.” When asked about how would it help students in their engineering career, he said, “As an engineer, students should model their innovations around simplifying the travails of the less privileged.”

To provide further experiences for students, Sudhair is also working on a program where they would live in a village for the summer – not to be “saviours” but to just live and learn with the people in the village to understand their concerns and life. This is also helpful, according to Sudhair, for developing graduates who can then take their education and give back to India and understand the human dimensions of science and technology.

I noticed that the blue skies above IIT Gandhinagar portended good astronomy, and I suggested to Sudhair that he should consider developing his astronomy capabilities at IIT Gh – a project I might be interested in helping with!

University of Ahmedabad and Liberal Arts

On February 22-23, I was able to visit Ahmedabad, where I was invited to speak to a group of assembled academic leaders from the University of Ahmedabad and the Manipal Group of Universities about Liberal Arts. The meeting was to envision the implementation of a new program in undergraduate liberal arts at University of Ahmedabad, which is a young university established in 2009 by the Ahmedabad Education Society (AES), a private Educational Trust. Ahmedabad University is expanding to include innovative interdisciplinary liberal arts programs for undergraduates. Pankaj Chandra, the Vice Chancellor, was a gracious host, and took me around Ahmedabad where we discussed a wide range of topics in higher education in India. A Hindi professor from U. New Delhi, Apoorvanad, joined us for many of our wide-ranging discussions and I really enjoyed getting to know Pankaj, Apoorvanad, and the others in the panel.

Our meeting included the following participants:

Yale-NUS College – Bryan Penprase (Director, Centre for Teaching and Learning and Professor of Science)

University of Chicago – Balaji Srinivasan

Manipal University

- Rajen Padukone (Group President – Manipal Education and Medical Group)

- Vinod Bhat (Vice Chancellor – Manipal University)

Ahmedabad University

- Pankaj Chandra (Vice Chancellor, Ahmedabad University)

- Devanath Tirupati (Dean, Ahmedabad University’s Amrut Mody School of Management (AMSOM))

- Parag Patel (Associate Dean UG Programmes, Amrut Mody School of Management)

- Saptam Patel (Assistant Professor – Communication Chair, BCom Programme)

- Payel Chattopadhyay (co-Director, Center for Future Learning)

University of Delhi – Apoorvanad (Professor of Hindi and Author)

The discussion was intense, thoughtful and insightful. We were able to develop strategies for developing a liberal arts program build upon individualized education for students, that includes dialog as a central element in pedagogy, and authentic assessments that can connect students to the larger world in their work. This would include using observations from students in presentations, writing position pieces to larger audiences for assignments, and displaying work in public settings. The larger concept of authentic assessment is vital for success, as it breaks away from exam-based pedagogy (which typically tests only lower-order learning outcomes) and allows for students to synthesize their own ideas, and to create new and original materials as part of their education.

We also recognized the need to communicate the goals and methodologies of this type of education to parents and to society, and to overtly push back against the definitions of “success” prevalent in Indian society – which tends to prioritize safe and high paying jobs as a primary consideration, often at the expense of developing student interests, and original capabilities.

Some photos of the campus are below. Ahmedabad University has an ambitious construction and hiring plan – and so the main building of the campus will soon be joined by large student center, and an arts and sciences building (currently a green field). A “maker space” is under construction and should provide a good space for students to build projects of all sorts – another outlet for their creativity, which will be a hallmark of the new University!

Astronomy2017 at the Singapore Art-Science Museum

On February 18 and 19, I was invited to speak at the Singapore Art-Science Museum during Astronomy2017, described as “Singapore’s Largest Astronomy Event.” The event was held at the beautiful Art-Science museum, a building that looks like a flower blooming out of the center of Singapore’s downtown Marina district. With my Yale-NUS College students, I was also able to share remote observations from our telescope in Chile known as LCRO. Since the event was held during the day, we were able to remotely operate our telescope and take live images from Las Campanas Observatory for the public. I was delighted to get help from our students – Jerrick Wee, Ricky George, Stephanie Chee, Gabriel Lek, and Joan Ongchoco. They were truly wonderful and did a fantastic job presenting our remotely operated telescope to groups of people who came by to see the live images. During the show we obtained images of Centuarus A, Omega Cen, and a few other spectacular Southern Hemisphere objects. Below are some pictures from the event!

Thomas Olsson and Pedagogical Competence

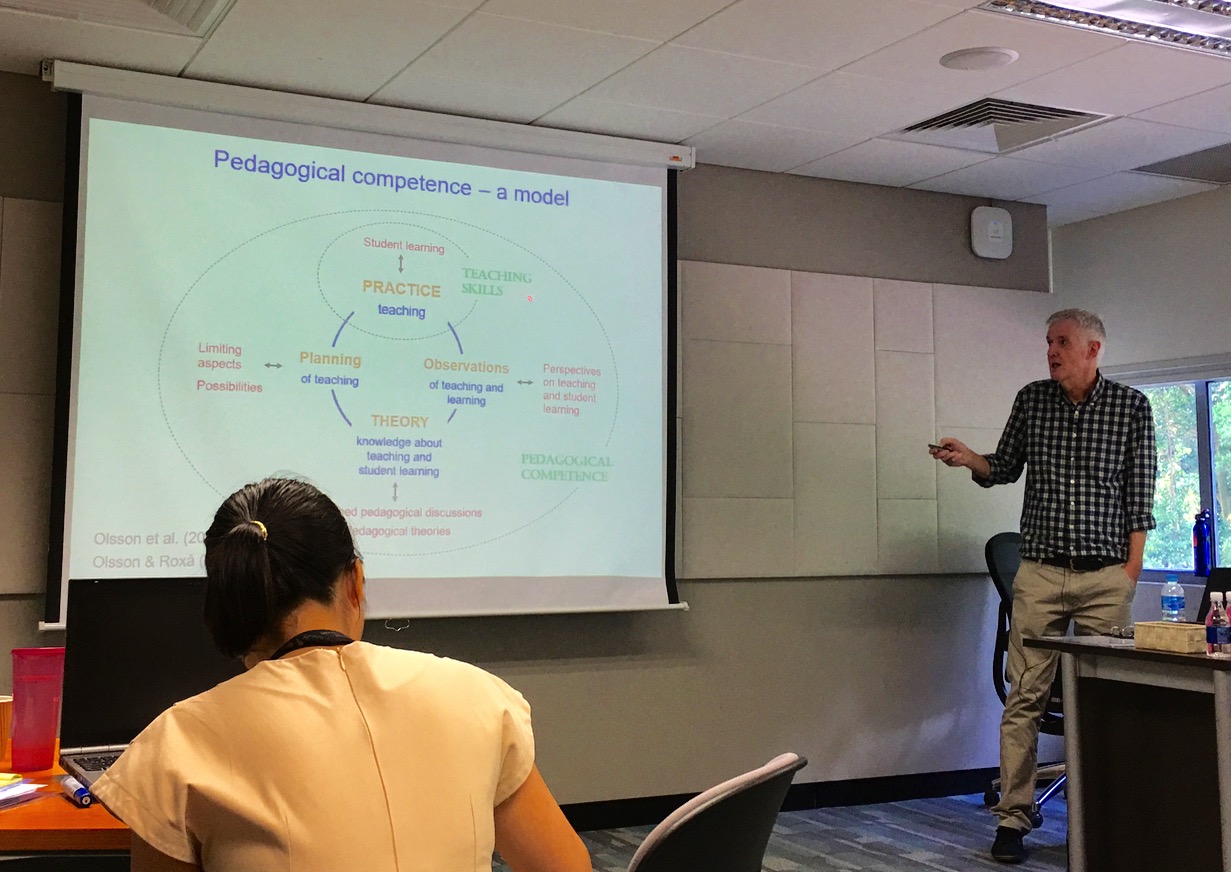

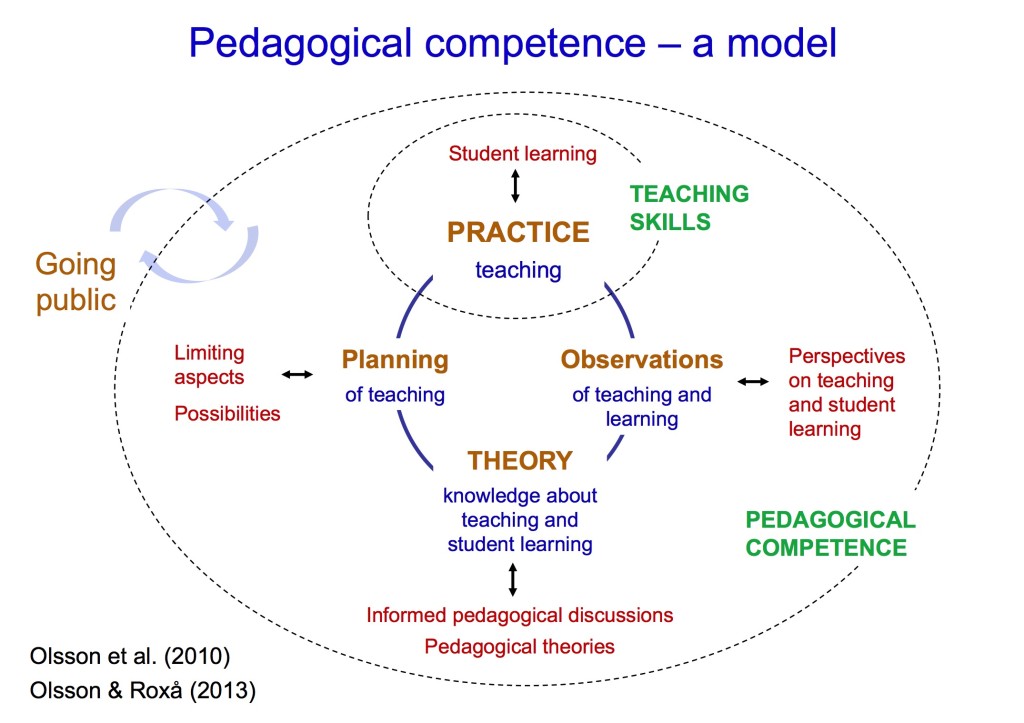

During late January, NUS hosted Thomas Olsson, from Lund University in Sweden, to discuss Academic Portfolios, and a broader range of topics related to SoTL and “Pedagogical Competence” – a term that describes a larger sphere of activity that includes not just the practice of one’s teaching, but a larger range of activities that includes observations of one’s own and other’s teaching, grounding in theory, and planning for more ambitious projects that links one’s practice to larger communities of practice – either disciplinary societies, or larger groups of faculty outside of one’s immediate department.

Thomas offered a wide range of discussions that included meetings with academic developers across Singapore, members of the NUS Teaching Academy, and a focused discussion of Portfolios and SoTL over a week. During the meetings we discussed the role of Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL) in promoting excellence in teaching. Thomas helped define what scholarship means in this context – and described a process of going beyond individual experience and institutions toward a more systematic set of observations of student learning, which can generate new knowledge that can be replicated and built upon. This effort can also be documented, made public, and subject to peer review – just as other scholarship in disciplines is done.

The progression from personal and local experience and knowledge toward a more public form of teaching is essential, Thomas argued, and he has made venues such as a pedagogical conference part of his work at the Engineering School at Lund. Within this conference are ~25 presentations from a wide range of faculty, who submit short papers that enter into a database. Over the years this database has become a valuable repository of the teaching culture within Lund University, and allows for a transfer of knowledge across time and courses. The program includes recordings of the talks which are placed online, as well as a “concept circuit training” where short discussions about teaching ideas.

Thomas also described how one can produce a more dynamic SoTL profile within faculty. The progression typically starts with a course that provides an “advanced pedagogical project” – which can be presented at a conference. This publication can lead to funding, which in Sweden is generously supported. The goal is to provide ways for sharing knowledge and experience – and to connect that sharing into public and scholarly presentations and publications. The goal is a “scholarly teacher” who is able to refer to literature on T&L, perform systematic observations, evaluate learning outcomes, obtain peer evaluation of their performance, as well as being an expert in their discipline and conducting their work as a professional. This definition draws from work from Trigwell et al, 2000; and Shulman, 2000. Along the way, the professor is able to break out of what Shulman calls “the island of pedagogical solitude.” Olsson also described four functions of the Scholarship of Teaching – to provide a basis for discovery, integration, application and to improve teaching. This structure was proposed by Boyer (1990) in his work “Scholarship Reconsidered.”

In addition to presentations in scholarly venues, the development of a Teaching Portfolio is a key ingredient in making teaching visible. At Lund University the portfolio is evaluated based on criteria that focuses on student learning (which requires teaching based on a learning perspective, integration between theory and practice, and a practice based on sound relation to students). The subject should be taught in ways that employ strategies to support students’ work toward increasingly complex and useful knowledge. The portfolio also documents the professional development as a teacher over time, with an effort to consciously and systematically develop students’ learning, and hopefully also includes a scholarly approach to teaching and learning that includes a reflection based on practice and educational theory, and an effort to integrate research into teaching and to “making findings public with a purpose of collaboration and interaction.” The goal of the process it to develop “pedagogical competence” which is a mix of activity that goes beyond one’s own classroom to integrate with research and the larger SoTL community, to make the results of your pedagogical practice accessible to others, and to enable it to be built upon or scaled up. The diagram below shows the schema for pedagogical competence.

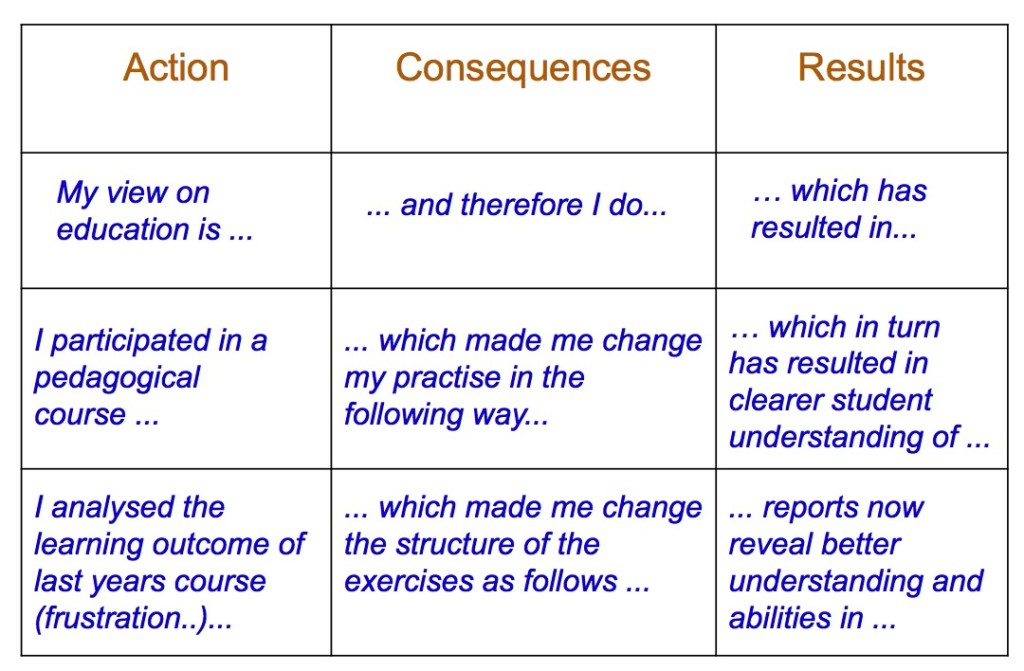

The teaching portfolio should include documentation of your teaching practice, along with a description and analysis of that practice, along with evidence that includes “artefacts from teaching and learning.” Thomas described the process as one of “concretion” – which describes significant teaching and learning situations, with a description of how you assessed and responded to the situation. A very useful breakdown in terms of “action,” “consequences,” and “results” was proposed to give a more complete description within the portfolio. The portfolio includes a description of the teaching practice along with concrete examples from the pedagogical practice. A good portfolio will not only describe what happened, but why, and explain observations, assessments, and a future vision of teaching. Within Lund University, portfolios are evaluated and they incentive excellence by giving grant funding to departments with excellent faculty (as judged by teaching portfolios) as well as modest raises for faculty who produce excellent portfolios.

American Astronomical Society Meeting

After a glorious holiday in Southern California, I presented a talk and a poster at the American Astronomical Society Meeting at the Gaylord Texan Resort in Sugarland, Texas.

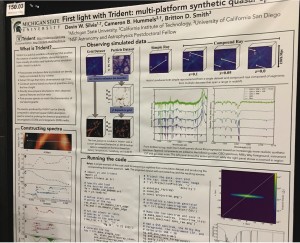

The meeting included a chance to learn more about what my former students had been doing – and it was wonderful to see how well they have progressed! At the meeting were Jason Rhodes (HMC ’94), who is now a chief project scientist at JPL for WFIRST and Euclid, and an amazingly nice guy; Alex and Lea Hagen (HMC ’11), who are just now finishing their PhD’s at Penn State and now world experts in interstellar extinction and galaxies, and Cameron Hummels (POM ’01), who is a postdoctoral scholar at Caltech, and author of an amazing software package for simulating quasar absorption lines from hydrodynamics data.

My presentation was a talk about the ZTF Educational programs, and more specifically our ZTF Summer Undergraduate Institute, where we take about 15 undergraduate astronomy researchers from across the country (and several countries) and form a tightly bonded cohort of future astrophysicists as they attend technical talks from Caltech professors and technicians, tour the Caltech optical laboratories, do hands-on experiments with Python, and observe with the Mt. Wilson 60″ and Palomar 200″ telescopes. Along the way we also have a banquet at the Atheneum at Caltech with a famous speaker (last year it was Aditya Sood (POM ’97), a former student and producer of the movie The Martian). We also have a lot of fun with competitive “scavenger hunts” on both Caltech and Pomona campuses, and a number of creative projects with the students. This Institute will be in its third year this year, and I have been very grateful for the help from Eric Bellm, ZTF project scientist, and a great group of Caltech postdocs, professors and engineers who supported the project, and others like Jay Pasachoff, Aditya Sood, and Sean Carroll, who have been part of our Undergraduate Institute. You can see my talk below as a PDF file.

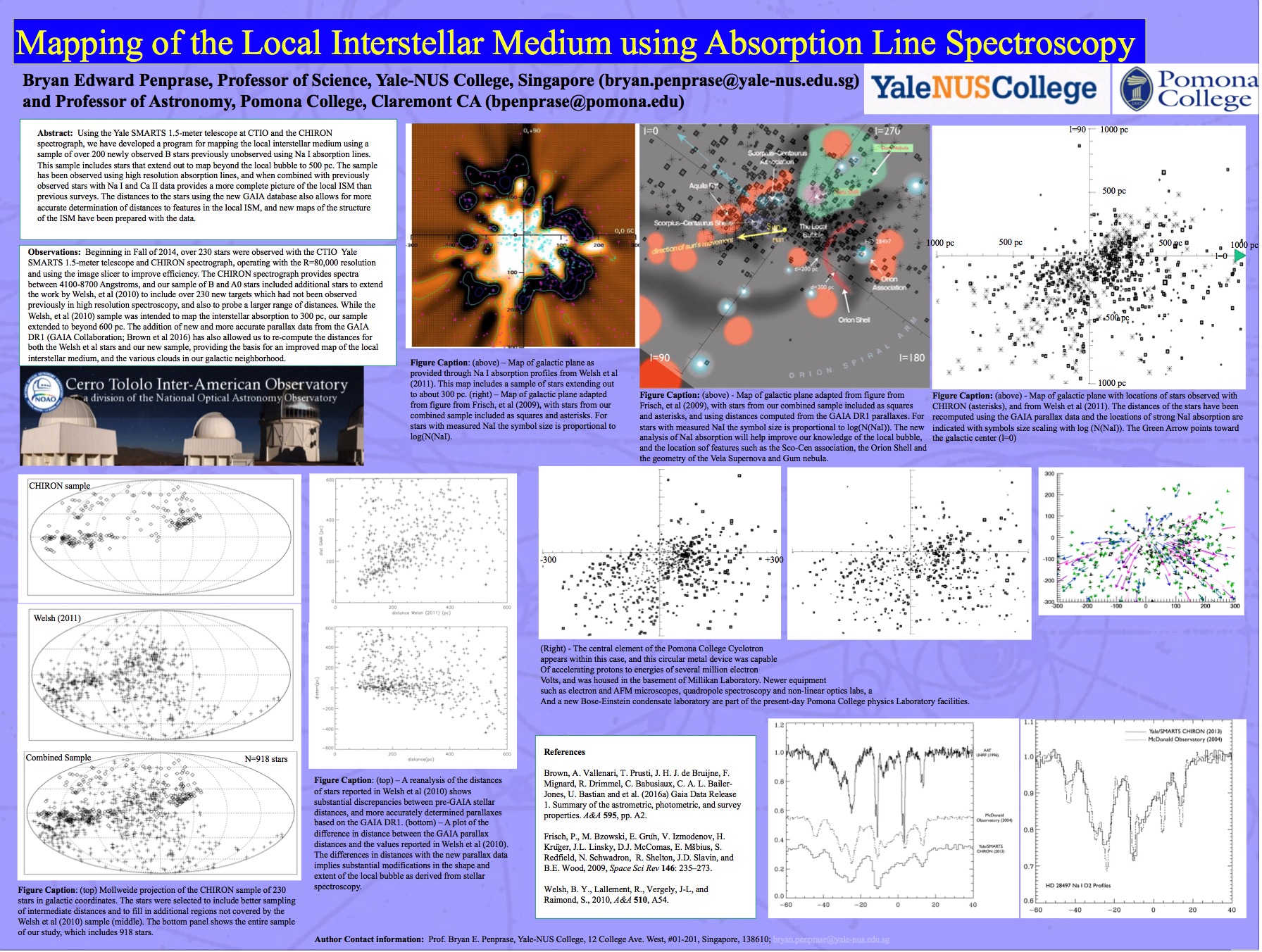

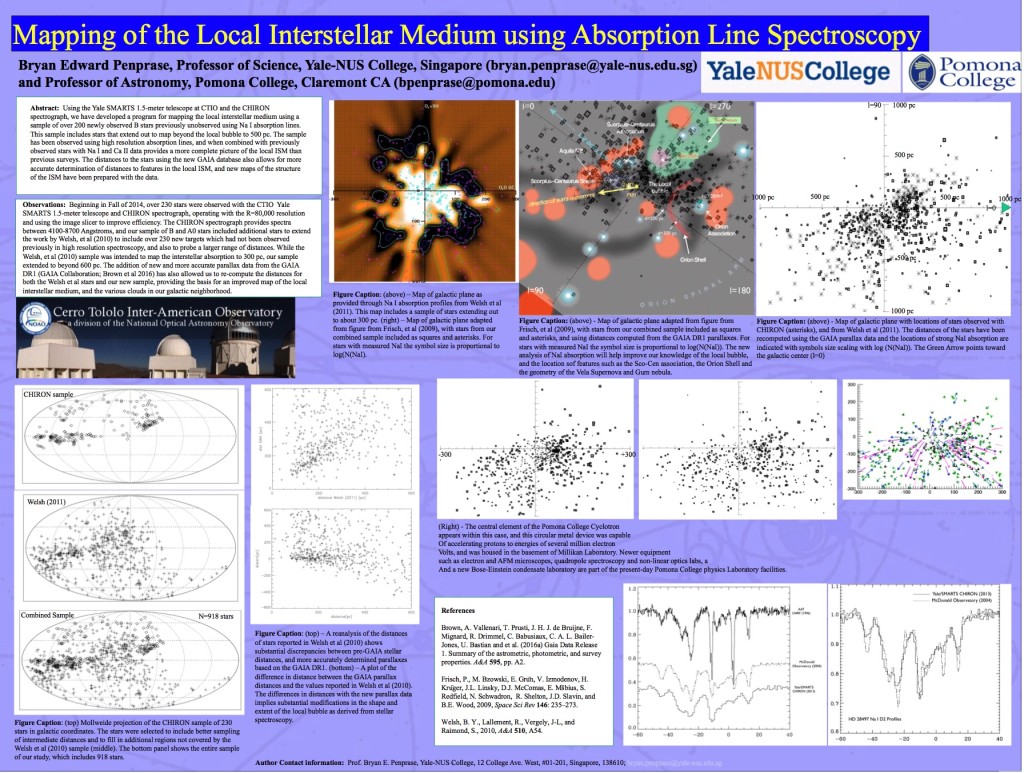

My other presentation presented my new research on spectroscopy of the local interstellar medium, which includes a new survey of Na I absorption to map the structure of the local galaxy. This project was conducted at Yale-NUS College using the Yale SMARTS 1.5-meter telescope and CHIRON spectrograph to observe the amount of interstellar dust and gas toward over 300 hot stars within about 600 parsecs of our location, to map out the structures and clouds that comprise the “local bubble” and other nearby star-forming region. One very nice new feature from this project is the release a few months ago of nearly a billion stellar parallaxes from the GAIA spacecraft. The parallaxes have enabled me to determine with unprecedented accuracy the distances to our various stars, and by combining our catalog of 300 stars with a larger sample in the astrophysics literature, we have the capacity to provide a map of the local interstellar medium, with unprecedented accuracy and depth. The survey and some of the preliminary results were described in my poster, which is below in both PPT and PDF formats.

Then just for fun, I include some of the pictures from the event, which is a mix of exhibitor booths, photos of the venues, and interesting slides from the talks I attended. Some of the talks I found most interesting were on primordial abundances as measured from quasar absorption lines (one of my other research programs), and a program known as “Science for Monks” that pairs scientists with Tibetan Buddhist monks for an intensive dialog on science and knowledge. In that talk, given by Tenzen, there was also a very nice depiction of Buddhist Cosmology that provides a detailed structure of that universe – something relevant to my book The Power of Stars, which is soon out in a new edition! Lots of interesting talks, people, and gadgets at the Astronomical Society meeting!

I also include these pictures in groups – Gadgets (equipment and telescopes of interest for Yale-NUS), Telescopes and Observatories (new initiatives in time-domain astronomy relevant to my ZTF work) and Ideas (Science talks about spectroscopy, and books of interest).

Gadgets – I am interested in getting new observatory capabilities for our Yale-NUS College, despite the terrible weather here in Singapore. My plan would be to get a small 14″ telescope which could be operated remotely, and test it on campus at Yale-NUS, then try to relocate it to a dark site in Malaysia or Thailand. If all else fails, there is a great radio telescope system available – which would be perfect for Singapore’s weather!

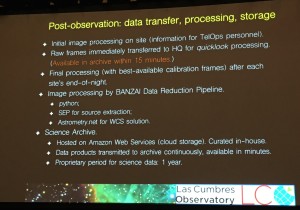

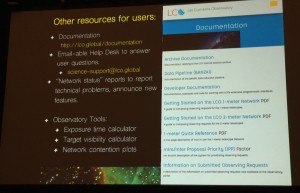

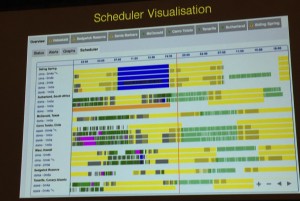

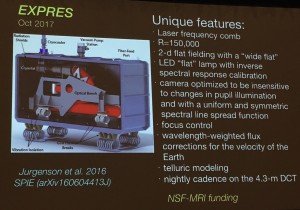

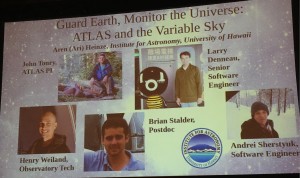

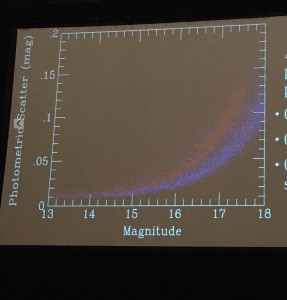

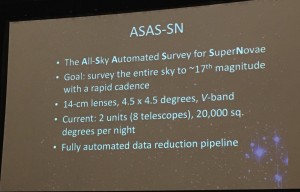

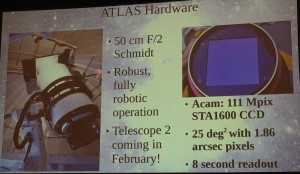

Telescopes – The small satellite known as CUTIE – designed by Brad Cenko for observing the universe in the UV is intriguing; also the EXPRES spectrograph for the 4.3-meter Discovery Channel Telescope – used by Deborah Fisher for exoplanet work at Yale. I also am a big fan of new robotic telescopes and saw great talks by the ASASN group, the U. of Hawaii ATLAS project ( a new pair of 0.5-meter survey telescopes), and of course the Las Cumbres Observatory with its amazing global network of 0.4, 1.0 and 2.0 meter telescopes. Below are some images from those talks.

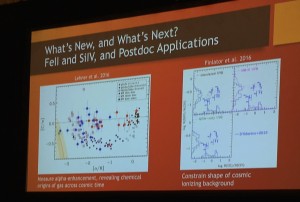

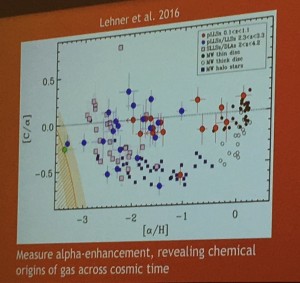

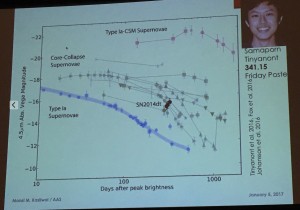

Ideas – Among the many interesting talks I attended, included one on new measurements of alpha-element enhancement in quasar absorption lines, which shows interesting variations of C/alpha at low metallicities, very nice Python packages for spectral typing of stars and for simulating QSO spectra, some nice results from the ZTF group, including a good talk about findings from PTF that may include a SMBH disruption event, and other interesting core-collapse supernovae, the Harvard Observing Project, which provides research observing experience for Harvard students who may not otherwise be involved in physics or astronomy (thereby encouraging them to join STEM fields), and an intriguing new book by Roger Penrose. Below are some images of those topics.

NASA Exhibit Opening at Singapore’s Art-Science Museum

My wife Bidushi Bhattacharya was invited to give a speech as part of the opening for the Singapore Art-Science Museum’s NASA exhibit, entitled “NASA – A Human Adventure.” She presented her new Space Technology company known as BSE-space, which is developing new space technology within Singapore – through developing cube-sats, organizing “astropreneur meet-ups,” training students in space technology, and developing an incubator of space-tech companies. Bidushi is a former NASA “rocket scientist” with over 15 years working on projects like the HST, JPL Mars rovers, the Spitzer Space Telescope, Herschel Space Telescope and the MISR observatory.

During the opening, we had a great chance to meet with other space-tech leaders, including Carter Emmart from the New York Natural History Museum (who presented the latest developments in the 3D Atlas of the Universe), and the Malaysian Lunar X-prize winner Mohd Izmir Yamin, who is working with Bidushi on new space-tech initiatives. Obviously I am proud of my wife’s amazing company – and we both are looking forward to further advances in “new space” within Singapore and Southeast Asia in the coming years! Below are some pictures from the event.

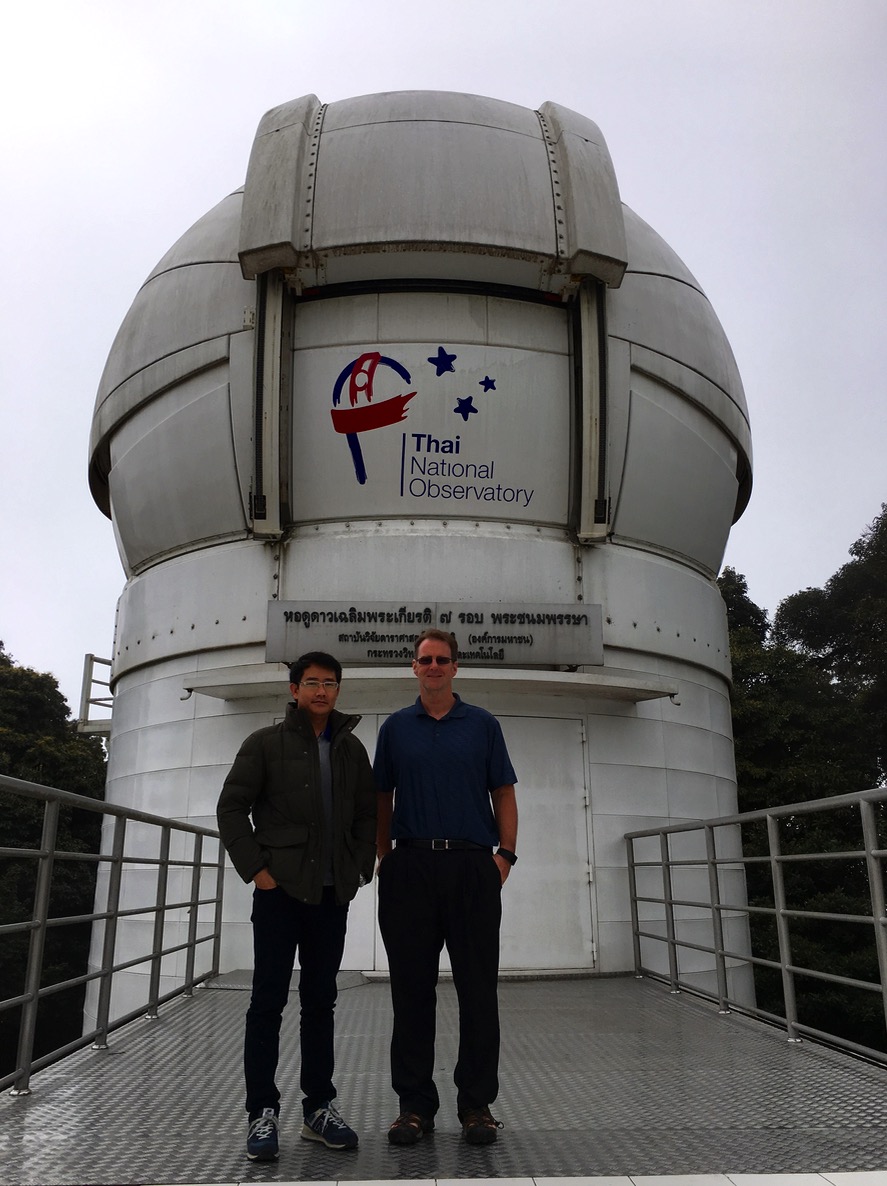

Visit to Thai National Observatory NARIT

On November 27-29, I was invited by NARIT Director Boonrucksar Soonthornthum to visit Chiang Mai, Thailand, and to give an astrophysics talk to the staff at the Thai National Observatory (NARIT). Boonrucksar also graciously offered to host a group of our Yale-NUS College students at NARIT in March 2017 during my upcoming Observational Astronomy class. The visit to NARIT allowed me to meet with the NARIT astronomy staff, learn about their ongoing research programs, and see first hand some of the advanced capabilities in Thailand for observational astronomy. The NARIT observatory includes a 2.4 meter telescope on Thailand’s highest mountain, and the NARIT staff kindly drove me out to the 2.4-meter for a tour, in advance of our Yale-NUS College trip.

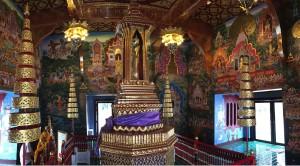

While in Chiang Mai, I had the privilege of touring several of the beautiful temples in the town. Some of these temples were constructed around 800AD when Chiang Mai was the capital of a powerful Buddhist empire. Below are some of the pictures of the temples in town.

After a 2.5 hour drive south from Chiang Mai, we visited the NARIT 2.4-meter telescope and had a wonderful lunch at the Royal gardens nearby. These photos show some of the impressive telescopes at NARIT and the beautiful gardens.