I was invited to attend the Association of Pacific Rim Universities Education and Research Technology Forum, on 17-18 November 2016, both representing NUS and Yale-NUS. The meeting had a theme of “Sustainable Technology and Learning Across Institutional Collaborations,” and brought about 80 educational leaders from the APRU Universities to a meeting at University Town, NUS – just next door to Yale-NUS College. The APRU was “established in 1997 by the presidents of California Institute of Technology (Thomas Everhart), University of California, Berkeley (Chang-Lin Tien), University of California, Los Angeles (Charles Young) and University of Southern California (Steven B. Sample)” [based on the description at http://apru.org/about/history-objectives-strategic-framework ].

The APRU consortium has grown to include 42 leading research universities based in 16 economies, with 110,000 faculty members, and 1.7 million students. The structure of consortium centers around programs that address Sustainability and Climate Change (hosted by UCSD), Multi-hazards (earthquakes, floods and volcanoes) which are common in the Pacific Rim region, Global Health (hosted by USC), an Ageing Gerontology Series, Brain and Mind Research in the Asia Pacific, and the Education and Research Technology Forum, which was the sponsor of our meeting. Additional programs include meetings of Presidents, Senior Staff, Provosts, Deans, CIOs, and additional exchange programs for doctoral students and APRU research fellows provide opportunities for students across the region.

During the meeting we heard talks from educational leaders from NUS, the University of Auckland (NZ), USC (USA), The University of Melbourne. the University of Sydney and ANU (Australia), the University of Malaya (Malaysia), the University of the Philippines (Philippines), University of Washington (USA), Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, and Tsinghua University (China). The international aspect of the meeting was very exciting as we heard perspectives on higher education that allowed for some cross-cultural issues. Some of the higher education issues are universal (need for improved use of technologies to enhance learning, limited resources, typical over-reliance of lecturing among faculty), and some issues had unique regional overtones. This was especially true in regards to management culture within a university, and the ways in which universities interact with their federal governments (typically through a ministry of education).

The program for the meeting is available at the site http://nus.edu.sg/apru/programme/ and includes both descriptions of the talks and downloads of the presentation files. Below is a summary of some of the key points from my viewing of the first morning of talks, with a sampling of some of the presentation slides.

Richard Katz gave a talk about Learning Analytics, and mentioned that “intellectual capital” in today’s economy is at a “high point of value” – more so than land, equipment and other more traditional components of capital. According to Katz, “we are living in highly disrupted times.” He then made the case for a very rapid pace of technological change in education, with avatars, online education, and other innovations changing how we do things entirely. He described a “de-peopled” learning environment, where artificial intelligence will make a much larger impact. He cited John Seeley Brown, who has written extensively about disruptive change, and mentioned that research universities “will be different in five years or we have problems.” He cited the Fourth Industrial Revolution and the various “exponential technologies” that produce accelerating change. Various educational and publishing efforts – Kahn Academy, WebMD, Huffington Post, eBay, were all mentioned as examples of how new ideas have replaced old industries. Universities however have what Cohen and March described as “Problematic Goals, Unclear Technology, and Fluid Participation.” He also noted the slow growth in tertiary education around the world and gaps in terms of funding and access that limit university effectiveness.

Katz urged “Collective Action” that will adopt a “21st century vision and goals.” This includes “expanding the pedagogical mix” to include a mix of learning modes, adopting neuroscience developments, and developing clear technology priorities to enable “moon shots,” “road maps” and “joint investment in development and testing across universities and sectors.” New business models were also needed, Katz suggested to enable TA’s and Adjuncts to be integrated more fully and to incorporate Artificial Intelligence “chatbots” into the learning process. In the end, universities need to “End Muddling Through” as students will outrun faculty, industry will continue to innovate, and soon the secrets of Learning and Teaching at Scale will be uncovered (with Universal Design as a key). But there is not time to muddle through, since education from others – Facebook, YouTube, Lynda.com – will only grow, even as “traditionalists are far too eager to label MOOCs a failed experiment.” Instead of the traditional focus on at risk students, or flashy initiatives in professional education, he urges a more consistent focus on fast-emerging technologies such as AI, VR, AR, chatbots, etc. which are not part of the HE mainstream’s conversation.

A talk from Sandra J. Christal, from the USC Marshall Business School, described how they are “Providing Collaborative Learning Opportunities for a Global World.” She highlighted their online MBA degree program – which is entirely online, and uses the Canvas LMS as their platform. She described how they used the AT&T building downtown (away from campus) to develop their program, and had separate offices and production studios. With 6 professors, she created 9 courses in a company known as Paragon. Five of these courses were put online, using Blackboard originally. Professors were paid a small stipend, and offered to spend 4-6 hours per week with an MOU to prepare course. Their pay increased if it included a report assessing the learning in the course. The five courses were integrated, and four professors were on staff to work with the 20-22 students/year that were enrolled. The program included separate tracks in Business Taxation, Supply Chain Management, as well as an MBA and MMLIS degree. The remarkable success of the course came from a dedication to providing the same quality in their online program as the on-campus program.

Some notable technologies described include the use of a digitally connected boardroom, the Zoom platform for online multi-party conversations, “Virtual Labs” for more detailed work, and a program known as YouSeeU which also helped with online multi-party conversations.

Abelardo Pardo from U. Sydney described “the Role of Data and Feedback at Scale” as developed in their undergraduate engineering curriculum. He described a “scholarly approach” where they listened to students, and created a system to provide the right kind of student feedback to promote learning. One citation he mentioned was by Kirshner, et al, 2016 on “The Cold Left-Overs of Inquiry-Based Learning” which is quoted below:

“ In 2006, Paul A. Kirschner, John Sweller, and Dick Clark wrote a famous/notorious (your choice) article on inquiry-based learning[1] (IBL). Well, it was actually also about constructivist[2], discovery[3], problem-based[4], and experiential learning[5]. In the article, the authors explained why, for example an inquiry-based approach is neither effective nor efficient. Since then, many articles and books have been published on the topic, both by IBL’s proponents and opponents. Interestingly, at the same time things started to turn. IBL moved towards “guided discovery”, problem-based learning approaches added “normal instruction” in order to improve learning outcomes, and so forth….”

“What the authors of the article call ‘guidance’ includes constraining (clearly defining task size), status updating (visualising learner progress), prompting (remind a learner that something needs to be completed), heuristics (explaining how something needs to be done), scaffolding (explaining and/or “taking over” complex parts of a task) and explaining (telling how something needs to be done). These techniques actually equal a general definition of good instruction or providing quality education.”

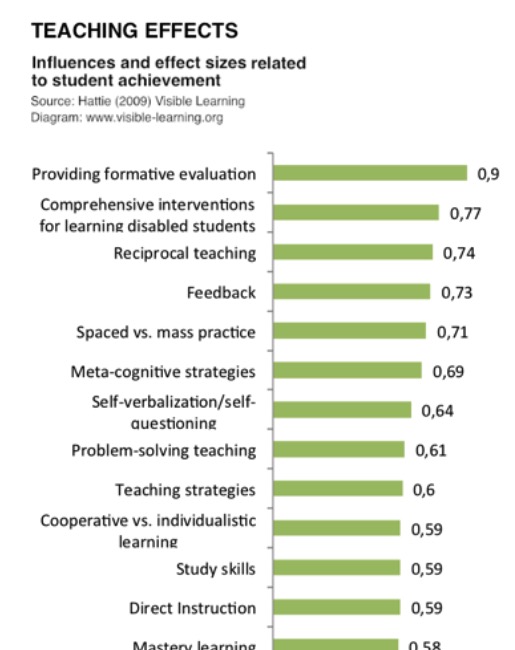

Pardo’s program began as U. Sydney recorded lectures and they wanted to develop ways to promote better assignment completion rates among students. Pardo cited Hattie’s Visible Learning (1999) who pointed out that student learning was enhanced with these top factors:

- Formative Evaluation

- Reciprocal Teaching

- Feedback

- Spaced vs. Mass Practice

- Meta-Cognitive Strategies.

This is summarized in the figure below:

Pardo also cited Hattie + Temperley’s 2007 work “The Power of Feedback” as an inspiration for his program. The problem is that it is difficult to provide effective feedback (which needs to communicate complex and qualitative information) to large numbers of students. The goal for his project was to create high-value feedback – that gives guidance. This was seen not as an administrative task but as a “pedagogical necessity.” Pardo’s talk also included a description of how feedback comes at many levels – analogous to Bloom’s taxonomy. It can include these levels of feedback:

- task level feedback (performance or understanding)

- process level feedback (what to do to understand or perform )

- self-regulation level feedback (detecting and directing effort)

- self level feedback (personal evaluation and affect)

Typically instructors give the first two levels of feedback, and then help students develop their own mechanisms for the last higher levels of feedback – which could also be called “meta-cognition.” He cited a paper by Bjork (2013) on Self-Regulated learning – Beliefs Techniques and Illusions and another by Dunlosky (2013) on study strategies. He urges an increase in personalization as a way to increase knowledge.

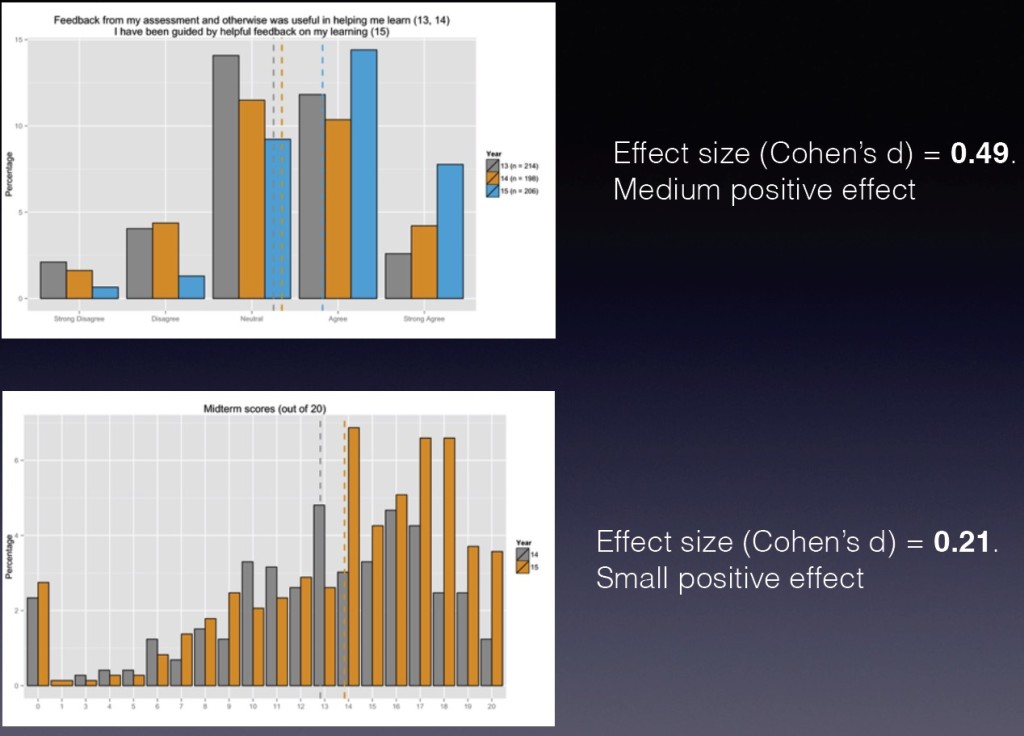

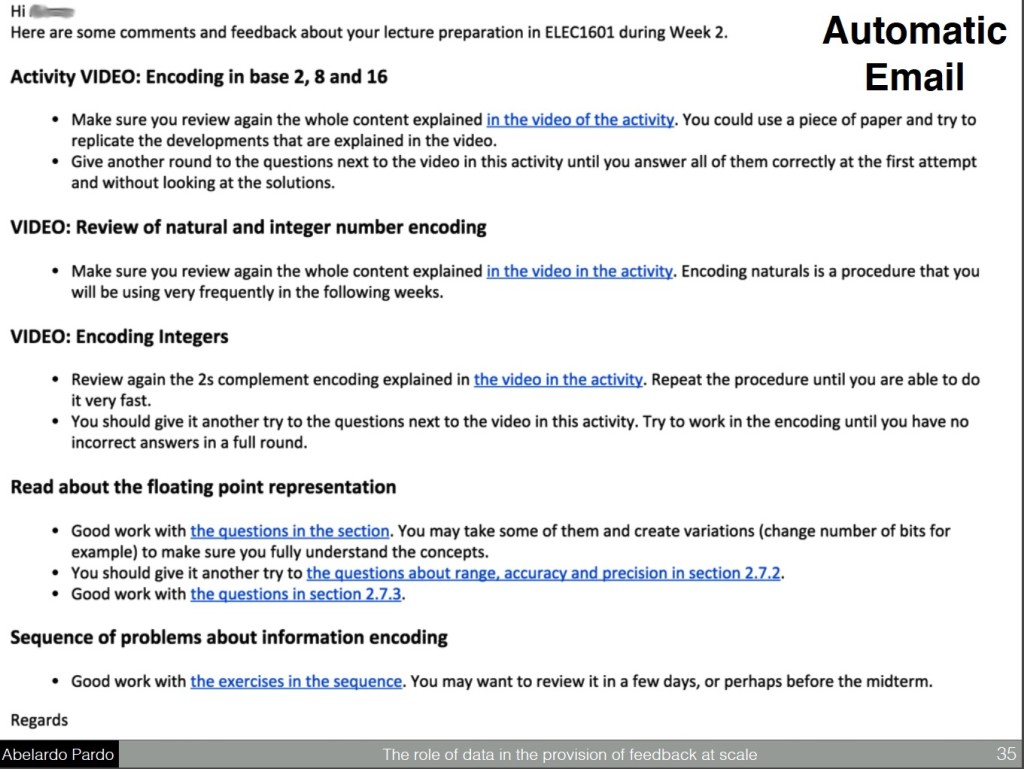

The work Pardo created is entitled “Generating Actionable Predictive Models of Academic Performance” and is one where they give students feedback in Engineering courses, and make use of “dashboards” to track student progress. He cited how instructors both need data on their students, and access to that data – so it is not “on Jupiter” but at their fingertips. His systems gives analytics on students, at scale, and gives feedback to groups of students, based on expert analysis. Students are broken into categories, and then these categories are given emails to these students giving them detailed feedback. The feedback helps them do better on assignments and he was able to track a performance boost which had a “Cohen’s d” measurement of 0.5. An example of his feedback that is sent to the students is below, from his presentation slides.